There are books that inform. There are books that inspire. And then there are books that bear witness—testimonies etched in time, written not merely with ink but with the residue of tears, prayers, and unwavering faith. Elder Charles Christon Sessanga’s “This Awesome Gospel” belongs firmly in this third category.

As someone who has served at Makerere Full Gospel Church through various capacities—from youth ministry to children’s ministry, and as a communications officer during the challenging COVID-19 period (2019-2022)—I have had the unique privilege of observing Elder Sessanga from both a distance and, occasionally, in those sacred corridor moments where wisdom is shared in passing. Yet it wasn’t until I read both “The Gospel of Power” by Rev. Hugh Layzell and this remarkable response that I truly understood the depth of legacy I had been walking alongside.

What Elder Sessanga has crafted is not simply a book; it is what he himself calls “a loud graphic way of saying thank you.” It is a son’s tribute to spiritual fathers, a witness’s testimony to miracles observed, and a curator’s careful preservation of a movement that transformed Uganda’s spiritual landscape.

The book opens with characteristic humility: “This is but a humble, symbolic work which should not be overestimated and taken for a comprehensive narration of all the events and achievements of the church.” Yet in this very humility lies its power. Elder Sessanga has given us something precious—a ground-level view of what happens when the Gospel takes root in turbulent soil.

Having read “The Gospel of Power,” a couple of years back I approached “This Awesome Gospel” with curiosity about how a national voice would respond to a missionary’s narrative. What I found was not contradiction but completion. Where the Layzells documented the planting, Elder Sessanga chronicles the harvest. Where they recorded the foundation, he celebrates the building still rising.

The genius of this work lies in its conversational intimacy. Elder Sessanga writes as one who was there—not as a distant historian but as an active participant. His memory of that “tall, wiry, exuberant young figure in a typically white T-shirt with a bow tie” who led him to salvation in 1961 isn’t just historical record; it’s personal testimony. When he describes Pastor Hugh Layzell’s favorite verse—Matthew 24:14, quoted with that “characteristic pause to let it sink”—we’re not reading about a preacher; we’re meeting a spiritual father through the eyes of a devoted son.

The Power of Eyewitness Testimony

What makes this book invaluable is its eyewitness quality. Elder Sessanga doesn’t merely tell us about the turbulent 1970s under Idi Amin’s regime; he lived through the church ban, worked under Javan (the foreman) with “wheelbarrow and mattock” digging foundations for what would become a sanctuary, and witnessed firsthand the miraculous provision that kept the gospel advancing when every natural circumstance screamed retreat.

His description of the Layzells’ deportation is heart-wrenching in its immediacy:

“If only my tears could be recorded and imprinted on this page as Dad Hugh narrated this very moment in time!”

This is not sanitized history. This is lived experience, still tender enough to provoke tears decades later.

Elder Sessanga’s literary style deserves special mention. For a man who describes this as his “maiden literary journey,” the prose reveals surprising sophistication. His poetic interludes punctuate the narrative with prophetic power:

“Christians either wailing or looking stunned

Or else asking why, what, where, and when

Time and fate strangling each other

Devil inflating blackness into hollowness

The Almighty ripping rocks like mushrooms

Impossibilities turning into ‘mashabilities’?”

These aren’t mere embellishments; they’re theological declarations wrapped in accessible language. They remind us that African Christianity has always had its own voice, its own cadence, its own way of declaring God’s faithfulness.

The Succession Narrative: A Model for Kingdom Building

One of the book’s most valuable contributions is its documentation of leadership transition. Elder Sessanga traces what he calls “the divine line”—from Rev. Hugh Layzell (the pioneer, 1960-1973) through Pastor Joshua Kamya Musoke (the sustainer through persecution, 1973-1991) to Pastor Fred Wantante (the builder and expander, 1991-present).

This isn’t just church politics; it’s a masterclass in succession planning that every ministry leader should study. Elder Sessanga shows how each leader brought exactly what the moment required:

- Layzell: The pioneering spirit, breaking new ground

- Joshua Kamya: The tenacity to survive persecution, building underground

- Fred Wantaate: The wisdom to structure, expand, and institutionalize without losing the fire

His description of Pastor Wantante’s transparent handling of a family crisis demonstrates the kind of pastoral courage that builds lasting trust: “Without much ado the pastor unwraps and expounds the mission… Almost instantly, a time bomb had been defused.”

Digital Platforms as Modern Pulpits

As a digital strategist, I resonate deeply with the book’s implicit message about documentation and testimony. Elder Sessanga understood something crucial: if we don’t tell our stories, they die with us. If we don’t document God’s faithfulness, the next generation inherits amnesia instead of legacy.

This is why I’m publishing this review on my blog. Digital platforms are indeed modern pulpits, and this testimony deserves amplification beyond the physical walls of Makerere. The story of how a small tent meeting under a mango tree in Nakawa (which still stands sixty years later!) became a movement that shaped Uganda’s Pentecostal landscape needs to reach every corner where digital signals flow.

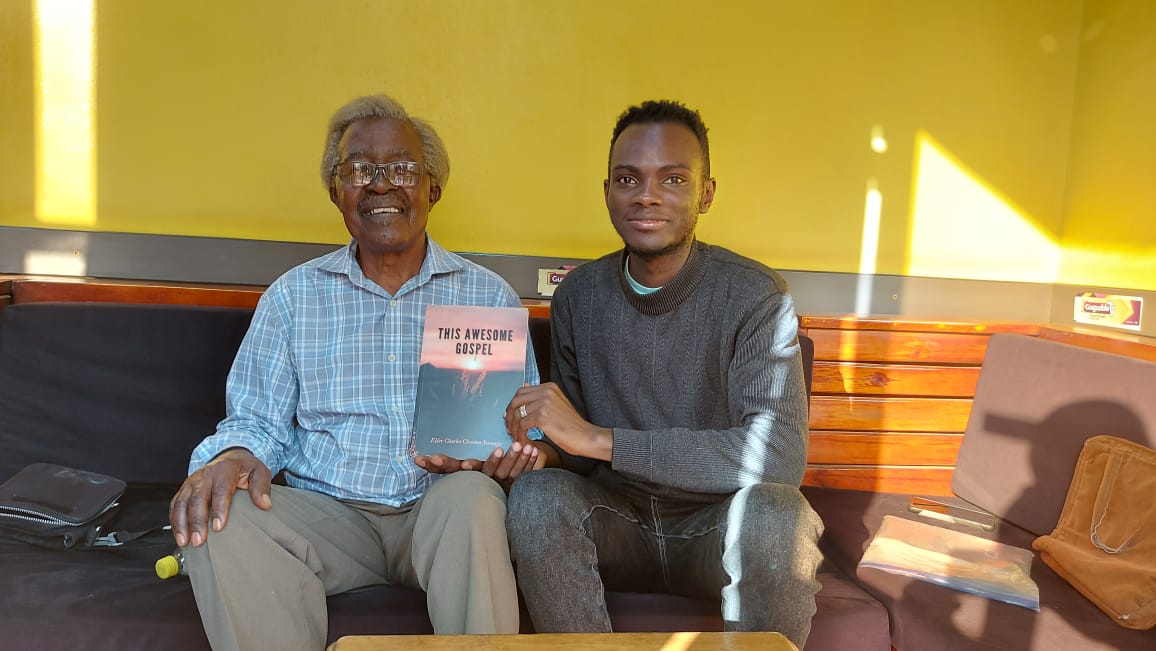

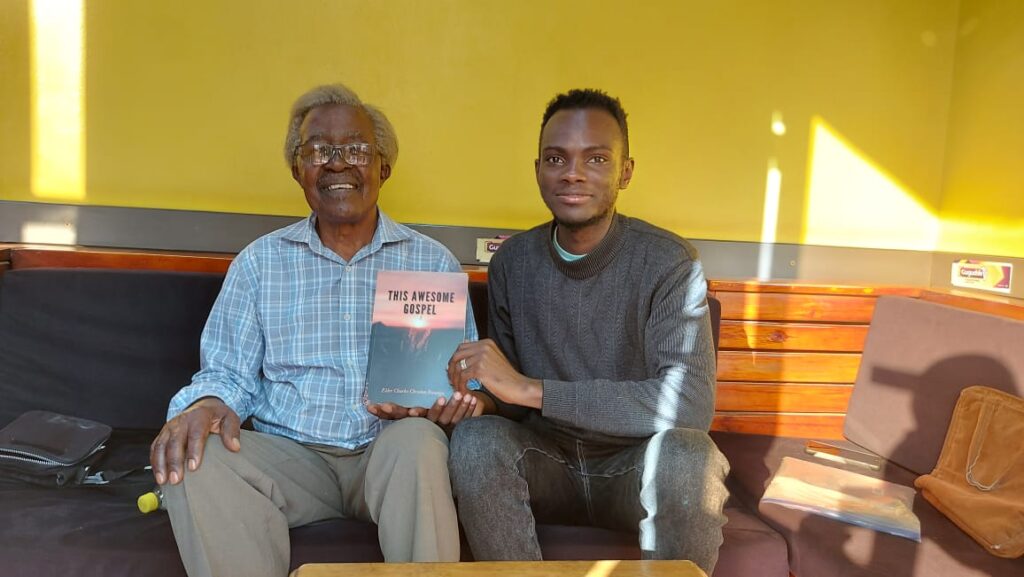

I must share a personal note. In 2024, I had the honor of preaching in three Sunday services at Makerere Full Gospel Church. It was a defining moment in my young ministry. After the service, Elder Sessanga approached me in one of those sacred corridor encounters. With the same discernment that marks this book, he identified my teaching gift and encouraged me to “pursue it diligently.”

Reading his book now, I understand that this is who he is—a spiritual father who has spent over sixty years in ministry, forty years teaching children in the classroom, and a lifetime teaching the body of Christ by example. His ability to see and call forth gifts in others isn’t accidental; it’s the fruit of decades walking closely with the Holy Spirit.

That prophetic utterance came from a man who has earned the right to speak. This book is proof of his qualification.

Constructive Reflections for the Author

With the deepest respect and as one who considers you a father figure, Mzee Sessanga, may I offer a few thoughts:

The Strength of Your Humility: Your insistence that this is “but a humble, symbolic work” is both endearing and understated. What you’ve created is a historical document of immense value. Future generations of African church historians will thank you for this work.

The Treasure in Your Memory: Your recollections—like the detail about Javan’s “cold sweet potato and warm black tea,” or Mom Audrey’s literary style—these aren’t peripheral; they’re the texture of real life that makes history breathe. Every memory you’ve included is a gift.

The Call for More: You mention limiting this account to “the small, manageable confines of Makerere Full Gospel Church.” While I understand the wisdom in scope management, I echo Elder Bukenya Paul’s foreword: there is still need for a comprehensive account. Perhaps this is volume one of a necessary series?

The Digital Legacy: This manuscript deserves amplification and wide distribution. But beyond print, it should be available digitally, with audio versions for those who would benefit from hearing your voice narrate these memories. The youth you taught for forty years in classrooms need to hear from the youth who dug foundations with a wheelbarrow in 1962.

What strikes me most about “This Awesome Gospel” is its theology of faithfulness. Elder Sessanga doesn’t give us a prosperity gospel or a triumphalism that ignores suffering. Instead, he gives us:

- A theology of presence: God with us in deportation, in prison, in church bans

- A theology of succession: God raising up the next generation

- A theology of patience: Sixty years of steady obedience

- A theology of joy: Even in tribulation, the church worships

His poetic reflection captures this beautifully:

“Composed and calm

In a corner of harm!”

This is African Christianity at its finest—tested faith that doesn’t deny suffering but transcends it through worship and witness.

Why Both Books Matter

Let me be clear: you need to read both “The Gospel of Power” and “This Awesome Gospel.” They are two sides of one miraculous coin.

The Layzells show us what obedience looks like when you leave everything to follow a call into the unknown. Elder Sessanga shows us what faithfulness looks like when you stay and build on foundations laid by others. Together, they model the complete picture of kingdom work—pioneering and preservation, planting and watering, starting and sustaining.

A Call to the Next Generation

As a young man serving in digital communications, I see this book as a challenge to my generation. We are excellent at creating content, building platforms, and achieving viral moments. But are we building anything that will still stand sixty years from now? Are we investing in foundations that future generations will build upon?

Elder Sessanga’s life and this book model something countercultural: the power of faithful presence. He didn’t chase platforms; he showed up faithfully for sixty years. He didn’t seek fame; he served quietly in music rooms, in classrooms, in church meetings. And now, in his eighties, his testimony becomes a megaphone that cannot be silenced.

This is the kind of influence worth pursuing.

There’s a recurring image in this book that haunts me beautifully: the mango tree at Nakawa Naguru market, under which the first open-air gospel meeting was held on May 14, 1960. Elder Sessanga tells us: “This mango tree still stands sixty years on.”

That tree is a prophet. It testifies that what God plants endures. The tent is gone. The small hall called “Kitawuluzi” may be forgotten by many. But the tree remains, and so does the church born under its shade.

“This Awesome Gospel” is Elder Sessanga’s way of pointing to that tree and saying: “Don’t forget. Don’t ever forget where God brought us from.”

Final Word: Gratitude

Mzee Sessanga, on behalf of a generation that has inherited what you and the pioneers built, thank you. Thank you for staying. Thank you for serving. Thank you for remembering. And thank you for writing it down.

This book is your legacy in print. But your greater legacy walks the halls of Makerere Full Gospel Church every Sunday, serves in ministries worldwide, teaches in schools, leads in businesses, and preaches from pulpits you may never see. We are all part of “This Awesome Gospel.”

Conclusion

Reading suggestion: Read “The Gospel of Power” first, then “This Awesome Gospel.” Take your time. Let the testimonies sink in. And if you’re able, visit that mango tree at Nakawa. Touch it. Remember. And carry the legacy forward.

This review is published as part of my commitment to using digital platforms as modern pulpits—spaces where faith, testimony, and legacy can reach beyond physical walls to encourage the global body of Christ.

Have you read “This Awesome Gospel”? What testimonies from your local church need to be documented before they’re lost? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

For inquiries about obtaining a copy of “This Awesome Gospel” or “The Gospel of Power,” please contact Makerere Full Gospel Church directly.